History of Family-centered Care and Family Systems Theory

- Research article

- Open Access

- Published:

Towards a universal model of family centered intendance: a scoping review

BMC Wellness Services Inquiry volume 19, Article number:564 (2019) Cite this article

Abstract

Background

Families play an important role coming together the care needs of individuals who require assistance due to affliction and/or disability. Yet, without acceptable support their own health and wellbeing can exist compromised. The literature highlights the need for a move to family-centered care to improve the well-being of those with illness and/or disability and their family caregivers. The objective of this paper was to explore existing models of family-centered care to make up one's mind the fundamental components of existing models and to place gaps in the literature.

Methods

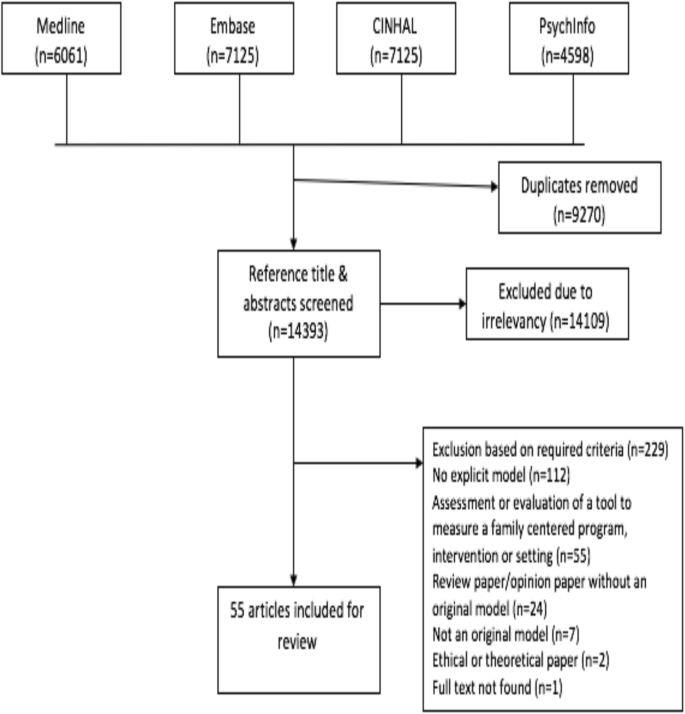

A scoping review guided past Arksey & O'Malley (2005) examined family-centered care models for diverse illness and age populations. We searched MEDLINE, PsycINFO, CINAHL and EMBASE for research published betwixt 1990 to Baronial 1, 2018. Manufactures describing the development of a family-centered model in any patient population and/or healthcare field or on the development and evaluation of a family-centered service delivery intervention were included.

Results

The search identified 14,393 papers of which 55 met our criteria and were included. Family-centered care models are nearly commonly available for pediatric patient populations (n = 40). Beyond all family-centered intendance models, the consistent goal is to develop and implement patient care plans within the context of families. Primal components to facilitate family-centered care include: i) collaboration between family members and health care providers, 2) consideration of family unit contexts, iii) policies and procedures, and four) patient, family unit, and health care professional pedagogy. Some of these aspects are universal and some of these are illness specific.

Conclusions

The review identified core aspects of family unit-centred intendance models (e.g., development of a care plan in the context of families) that tin can exist applied to all populations and care contexts and some aspects that are affliction specific (e.g., affliction-specific educational activity). This review identified areas in need of further enquiry specifically related to the relationship between intendance plan decision making and privacy over medical records within models of family centred intendance. Few studies have evaluated the impact of the diverse models on patient, family unit, or health organisation outcomes. Findings can inform move towards a universal model of family unit-centered intendance for all populations and care contexts.

Groundwork

Families play an integral role providing care to individuals with health conditions. As the number of individuals facing chronic illness continues to ascent worldwide, there is a timely demand to increment recognition of the care input made by family members. Well-nigh half of Canadians aged xv years and older take provided care to persons with illness and/or disabilities [1]. Definitions of caregivers vary, only in full general they are an unpaid family unit member, close friend, or neighbor who provides assist with every day activities, including hands-on intendance, care coordination and financial management [ii]. Nosotros use the term caregivers to reverberate this definition. We use the term family unit to include the patient, caregiver(s) and other family members. When caring for patients with progressively deteriorating conditions and increasing care needs, over time, caregivers perform more complex care duties similar to those carried out by professional person wellness or social service providers [iii, iv]. Thus, caregivers play an of import role in the care of persons with illnesses or disability beyond the entire disease trajectory.

Caregiving can be associated with negative outcomes. Caregivers' physical and mental health, financial status, and social life are oftentimes negatively impacted, regardless of the care recipients' affliction [2,3,4]. As a effect, the quality and sustainability of intendance provision at home may exist threatened [5, 6]. Policies and programs to help sustain the caregiving part may reduce the negative consequences of caregiving and optimize care provision in the dwelling.

The need to back up caregivers to minimize negative outcomes and optimize the intendance they provide has received considerable attention in contempo policy initiatives. In 2007, the Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care (MOHLTC) announced the Crumbling at Habitation Strategy, "to enable people to continue leading salubrious and contained lives in their ain homes" [7]. The strategy implies a shift away from institutional (east.g., long-term care) care towards home care, using population-based funding allocations to offer health and social services to seniors and their caregivers [7]. This is similar to initiatives in other provinces, such as British Columbia's Choice in Supports for Independent Living (CSIL) program, introduced in 1994. As these strategies place increasing demands on caregivers, a broader initiative, the National Carer Strategy launched in 2008 and updated in 2014 articulates the need for universal priorities to support caregivers [8]. Changes in Canada are echoed in other countries, including Sweden and Vietnam [9,10,11]. These initiatives aim to facilitate a collaborative activity program to support seniors through policy.

Family-centered care has been proposed to address the needs of not just the patient, but besides their family unit members. To date, family-centered intendance has been defined by a number of organizations. The Institute for Patient- and Family-Centered Care (IPFCC) [12] defines family-centered care as mutually beneficial partnerships between health care providers (HCPs), patients, and families in health care planning, delivery, and evaluation. Alternatively, Perrin and colleagues [thirteen] define family unit-centered care every bit an organized system of healthcare, education and social services offered to families, that permits coordinated care across systems. In palliative care, family-centered care is defined past Gilmer [14] as a seamless continuity in addressing patient, family unit, and community needs related to final atmospheric condition through interdisciplinary collaboration. In the broadest scope, the notion of family-centred care embraces the view of the intendance-client as the patient and their family, rather than simply the patient [14].

Building upon existing definitions, models of family unit-centered care have been proposed for a number of patient populations. The family-centered approach to healthcare delivery, adult most notably for pediatric-care, values a partnership with family members in addressing the medical and psychosocial health of patients. Parents are considered experts concerning their child'southward abilities and needs [xv, sixteen]. In the context of disquisitional intendance, family unit-centered interventions may decrease the strain of caregiving in families during a crisis [17]. In the context of stroke, a family-centered approach to rehabilitation showed an improvement in developed children caregivers' low and wellness status 1-yr post stroke [18]. Other researchers have argued that family unit-centered care offers an opportunity to support families and strengthen a working partnership between the patient, family, and health professionals during end of life intendance [19]. With an crumbling population and a growing number of people living with chronic illness, family unit-centered care can help health intendance systems to provide back up and improve quality-of-life, for patients and their families.

To date, there has been no synthesis of fundamental components of original family unit-centered intendance models beyond all illness populations. Therefore, the objective of this paper was to conduct a scoping review of original models of family-centered intendance to decide the key model components and to identify aspects that are universal beyond illness populations, and intendance contexts and aspects that are disease- or care-context specific. This paper also aimed to place gaps in the literature to provide recommendations for future research. A scoping review was selected as optimum because its goals are to generate a contour of the central concepts in the existing literature on a topic and place gaps in the literature [20].

Methods

We used a scoping review methodology guided by Arksey & O'Malley [21] to gather and summarize the existing literature on family-centred care models.

Search strategy

A literature search of MEDLINE (including ePub ahead of impress, in process & other non-indexed citations), CINAHL, PSYCHInfo and EMBASE databases was conducted. The search terms "family-centered", "family unit-centred" were applied. The search strategy utilized a narrow focus due to the high degree of noise boosted keywords generated. All searches were limited to English language publications from 1990 to August one, 2018. We did non limit the patient population every bit we believed that the expected number of models in any sub-set of populations would be low. Searches were conducted past an Data Specialist. EndNote was used to organize the literature and assist with removal of duplicates. See Additional file 1 for an example of the search strategy.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Inclusion criteria

-

The focus of the article was on the development and/or evaluation of a family-centered model or a family-centered service delivery intervention

-

The commodity considered healthcare providers' communication/interactions with patients and families

-

The focus of the article was on the development of a family-centered model in any patient population and/or location of care (i.e., acute care hospital, inpatient rehabilitation, community, institutional long-term care).

For the purposes of this paper, we used The Agency for Clinical Innovation (ACI)'s definition of a model of care: "the way health services are delivered" ([22], p., three). The definition includes where, past whom and how the intervention is delivered.

Exclusion criteria

-

The focus of the commodity was an assessment or the evaluation of a tool that measured the degree of family-centeredness of a program, intervention or setting and non the evaluation of an original family-centered intendance model

-

The article considered but interactions between family members

-

The article was a review paper that did non propose an original model of family-centered intendance

-

The article pertained primarily to upstanding issues or the theoretical understandings of family-centered care

-

The article was focused on training healthcare providers on how to deliver family-centered care and did not offer an original model of family-centered care.

-

The article reviewed or discussed simply the history, implications or rationale for family unit-centered care (eastward.k., the study conclusions suggested the need for a model of family-centered care)

-

The article described a patient-centered care model that just included word of family unit interactions

-

The focus of the commodity was on the development of a family-centered model exclusively for social back up, rather than in a clinical, health-care context.

Study pick and charting the information

The search identified 14,393 papers. One of the authors (G.M.G.) reviewed the citations and abstracts using the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Two other individuals reviewed 30% of the retrieved abstracts. Any discrepancies were discussed until consensus was reached. The inclusion/exclusion criteria were modified as needed to raise clarity (final inclusion/exclusion criteria aforementioned). Total-text articles of all potentially relevant references were retrieved, and each was independently assessed for eligibility by one of the authors (K.1000.K.) and the 2 other reviewers. There was 100% cyclopedia between all reviewers on this 2d step. Reference lists of the included articles were reviewed past one of the authors (Thou.M.Thou.) and the 2 other reviewers, but no additional articles were added to the review.

Data were extracted by the lead author (K.Thousand.One thousand.) and the abstracted data content was reviewed for accuracy past the two other reviewers. Data were extracted relating to elements of the family unit-centered care model including details of the targeted population, objectives, intervention (if applicable), central findings and desired outcomes of the model. The fundamental components of the models were systematically charted using a data charting form developed in Microsoft Word with a priori categories to guide the data extraction (run across Additional file 2).

Data synthesis

The purpose of this scoping review was to aggregate the family unit-centred model descriptions and nowadays an overview of the key elements of the models. Methodological rigour of the publications was non examined, as consistent with scoping review methodologies [21].

The extracted data were collated to identify central components of models of family-centered care. K.M.One thousand extracted the data and J.I.C reviewed the extracted data. K.M.Yard and J.I.C then followed qualitative thematic assay using techniques of scrutinizing, charting and sorting the extracted information according to crucial nuances of the data, and this was summarized into descriptive themes characterizing model components [21, 23]. Data were synthesized using summary tables with tentative thematic headings. Themes and potential components of family-centered care models were discussed betwixt K.M.Thousand and J.I.C until consensus was achieved, and final themes were adult. When discussing themes, K.M.K and J.I.C analyzed the data within and then across different patient populations (diagnoses), age groups (pediatric vs. developed literature), and care contexts (e.chiliad., astute care, community care) to identify aspects of models that are universal (i.due east., do not differ across populations and intendance contexts) and aspects that are disease-specific. Final themes were then discussed with all authors. These themes represent answers to our study objective.

Results

50-v articles were included in this review (encounter Fig. ane). The majority of articles were not grounded in empirical research but proposed models for family unit-centered care and offered practical suggestions to inform implementation (91%). Of the nine empirical studies, iv articles (seven%) described randomized control trials (RCTs) and one (ii%) described a pre-test, mail-test evaluation of their model. Three of the models tested in RCTs were developed to support families at the end of the patients' lives, with the other model focused on behavioural change as function of childhood obesity treatment. The article describing a pre-exam, post-examination evaluation aimed to reduce alcohol and drug employ through positive peer and family influences. Another written report used longitudinal experimental quantitative design to measure the touch on of their family-centered intendance model over two time points, using t-test assay [24]. These studies demonstrated benefits of the models including enhanced feelings of mastery and empowerment for family members in care planning through skill building [24,25,26].

Search Selection

Two articles (3%) examined the feasibility of applying the concepts of family-centered models into practice. Eight articles (14%) described case studies of an implemented model that included families and children with complex medical needs in palliative and sub-acute settings with weather including HIV, cancer and stem-cell transplantations. Some other described patients and families in cardiac intensive care units (CICU) after operative procedures. Nine (xvi%) articles were literature reviews on FCC that lead to the clarification of a single hypothetical family unit-centered care model, merely did not review all existing FCC models. I article (2%) compared HCPs' roles in traditional models of care with their roles the family-centered model.

Out of the 55 included papers, forty (73%) were explicitly designed for pediatric care recipients. In the pediatric literature, family-centered care models were proposed for a variety of populations which included, simply were non limited to, cancer (north = v), AIDS/HIV (due north = iii), motor dysfunction (east.1000. cognitive palsy) (due north = 3), non-illness specific disabilities (n = 2), obesity (n = 3), asthma (n = i), oral disease (1 newspaper), trauma (northward = 2), autism (n = 1) and transplant recipients (n = one). 18 studies did not report on a specific population. In adult populations, models have been presented for palliative care (north = 3), middle failure (n = 1), mental health (n = 1), cancer (n = 1), age-related chronic atmospheric condition (n = 1) and unspecified populations (n = eight).

Many of the family unit-centered intendance models have been developed for a variety of care contexts (e.g., community, acute intendance) and incorporate a diverseness of wellness care professionals. Care contexts included home/community care, acute hospital wards, emergency departments, critical care units, inpatient rehabilitation units and palliative care units. Professionals identified in the models primarily included nurses, social workers, physicians and nutritionists. In some models, psychologists, rehabilitation therapists and chaplains as well were included. The core elements of FCC models did not differ by diagnosis, age or care context. This suggested that some aspects of FCC models were universal. We use the term "universal" to refer to this notion of loftier-level concepts that tin can exist applied across disease populations, ages and intendance contexts. Universal and illness-specific aspects of FCC volition be discussed in detail below.

Thematic analysis revealed a universal goal of FCC models to develop and implement patient care plans within the context of families. To facilitate this aim, family unit-centered care models require: 1) collaboration betwixt family members and health intendance providers, 2) consideration of family contexts, 3) educational activity for patients, families, and HCPs, and 4) dedicated policies and procedures. Figure 2 provides a graphical overview of the primal components of FCC. This figure highlights the overarching goal of FCC models and the key components required to help facilitate this goal including both universal and disease-specific components.

Universal Model of Family-Centered Care

Overarching theme: family-centred intendance plan development and implementation

This overarching theme describes the universal goal of family-centered intendance models to develop and implement patient care plans that are created within the context of unique family situations.

All 55 models supported the evolution of family-centered intendance plans with specific short and long-term outcomes [27,28,29]. Patients, families and HCPs were considered key partners who should contribute to the clarification of intendance plan goals [30,31,32,33]. Care plans should consider the twenty-four hours-to-day ways of living for patients and families [34,35,36,37,38,39,40] by encouraging the maintenance of home routines [41]. Potential goals identified included achieving family unit and patient identified functional milestones like a new motor skill (e.yard., running) [30]; decreasing delays or complications at hospital belch [42]; improving patient and family satisfaction with care [40,41,42]; and improving caregiver support [43]. Patient involvement in care plans was acknowledged as conditional upon the patient's capacity to participate (it may exclude young children, people with illnesses affecting their noesis, etc.). From the initial diagnosis, the models championed that all members of the patients intendance team should arm-twist families' perspectives regarding priorities, families' needs and concerns, and their abilities to provide care [14, 29, 37, 44,45,46,47,48]. Understanding families' needs and priorities was deemed important and as contributing to realistic and amend-divers outcomes [24, 45], besides every bit important to raise families' abilities to back up the plan and optimize patient outcomes [41, 49,50,51].

The models also emphasized that HCPs and family members should share in the implementation of the intendance plan. Intendance delivery should embark when anybody is in understanding with the care plan [42]. Information technology was noted that family members should be encouraged to communicate any issues or priorities they accept regarding care to HCPs [27, 44]. Family members of relatives who are inpatients also should exist involved in discharge planning, such as describing their concerns and ability to perform care duties [42] so as to troubleshoot and optimize care in the community. Some models noted that intendance plans can be made achievable by breaking them down into smaller steps for the family [27]. One model also hypothesized that monitoring the success of the intendance plan has the potential to optimize service utilise by bridging service gaps and eliminating whatsoever duplication of resource [52].

Model components

In addition to the overarching theme related to care plan development and implementation (described higher up), other cardinal model components needed to facilitate family-centered care plans were identified. These encompassed collaboration and advice; education and back up; consideration of the family context; and the need for policies and procedures.

Collaboration

Family unit-centered care models highlighted collaboration between HCPs, patients and families as central in the development of care plans. Collaboration was noted as beingness required across the illness and care trajectory [53] to enhance patients' and families' abilities to maintain control over the patient'southward intendance plan and commitment [54], peculiarly as care becomes increasingly complex [55].

Many of the family-centered care models offered some insight into how families and HCPs could work together in the delivery of intendance beyond the intendance trajectory. Trusting [54], caring and collaborative relationships [44] between families and HCPs were identified as key and efforts should exist undertaken to cultivate them. In this collaborative relationship, HCPs were encouraged to relinquish their function as a single say-so. Some authors fifty-fifty argued that families should have controlling dominance to decide upon the office and the degree of interest of HCPs in developing care plans [28]. Attharos and colleagues [55] farther suggested that family-centered care models should have divers roles for each family unit member, the patient, and all involved HCPs. All roles are essential to the evolution of intendance plans [56].

Communication

Family unit-centered care models were thought to better facilitate advice and exchange of information and insights amid family members, patients and HCPs related to the development and delivery of care plans [54]. One model suggested that clinicians should offering care options and patients and families should advocate for patient preferences and family values [57]. The substitution of information was encouraged to exist open, timely, complete and objective [27, 55].

The models encouraged HCPs to use a diverseness of strategies to communicate with and support caregivers and patients, including interdisciplinary care and diagnostic reports, community follow-upwardly in-person or by virtual meetings, and resources notebooks listing community supports to assistance care for the patient [29]. HCPs were also encouraged to communicate disease-specific information to help patients and family unit members brand appropriately-informed disease-related decisions [32, 39, 57].

Didactics

Education about care provision and the disease was deemed necessary to enable family-centered intendance. Teaching was typically approached from the concept of common learning, whereby patients, family members and HCPs all learn and back up each other [38, 54]. In general, models advocated for preparation of HCPs to finer elicit information and communicate with patients and family members. This was idea to decrease anxiety and increase command for patients and caregivers [14, 32, 58, 59].

Various researchers posited ways to best provide educational activity near the illness and care provision to patients and families. Connor [sixty] suggested that written information, describing the family unit-centered approach to intendance should be provided to patients and caregivers. Further, all information should exist presented at a language level that is understandable to the family and patient [42, 43, 60], which means minimizing technical (east.g., medical) jargon [59].

Didactics was though to be ongoing, meaning that it often doesn't finish when a patient is discharged from an inpatient setting. Models highlighted a need to establish methods to continue educating caregivers beyond inpatient care [49], such as by providing the patient and family with a follow–up care plan after discharge and possibly follow-upwards contact by HCPs [33]. Appropriately communicated education is believed to foster a sense of trust [42] and help patients and family members become more knowledgeable. Equally a event, patients and families were idea to get more independent in making informed treatment decisions [14, 35, 37].

Some models noted that patients and their family members find information technology helpful to learn from other patients and caregiver peers [32]. Peer sharing of mutually supportive resources and other experiences related to living with an illness or providing care tin serve as an important means of improving cognition about support resources [32] and enhancing emotional support [lx, 61]. This was thought to be possible as part of family unit centered care models by care teams helping to cultivate friendships and general peer support with other families in similar caregiving situations (for instance, those caring for intendance recipients with the same disease). Other mechanisms to offering peer support could include patient and caregiver support groups, workshops, grouping retreat trips, and shared respite care [fourteen].

Family unit back up needs

Family members may experience a negative impact on their own well-beingness equally part of the ongoing demands of caregiving. Recognizing that families are often psychologically stressed and can accept difficulties coping [59], family-centered intendance models emphasized support for family members' well-being [62]. Supporting families often included emotional support and providing education and training on care delivery that takes into business relationship caregiver needs and preferences. Family-centered models acknowledge that caregivers are experts in matters concerned with their own well-existence [47]. HCPs were idea to support caregivers' by providing didactics to foster caregivers' confidence in their ability to provide care and develop care plans.

Family-centered intendance models emphasized that care recipients function all-time in a supportive family environment [41]. Identifying the impact of the illness on the patient and the family is crucial to providing emotional support [42]. At a minimum, information almost support needs should be gathered from both patient and family [63]. Particularly in pediatric patient populations, authors spoke of identifying types of back up that are based on the patient's developmental capacities [64] and needs, while too taking into consideration the social context of the patient and family's life [48]. Support needs can be determined through well-designed, semi-structured activities, including questionnaires [48] and discussions with the family.

Health systems utilizing a family unit-centered care model were thought to help sustain caregivers by providing them with resources to support their caregiving activities [65]. Goetz and Caron [49] state that organizational support should brand existing health service community resources more family-centered by considering the family unit in all aspects of program delivery. Topics that need to be addressed by services offered to family members included, mental health, home care, insurance/financing, transportation, public health, housing, vocational services, education and social services [thirteen].

Consideration of family context

Family was conceptualized in different means across models. For example, some models described including the family unit-as-a-whole (every family member, not merely those that provide care) [63, 64], whereas others described the family as those who provide care [44]. Authors highlighted that families have 'the ultimate responsibility' [63] and should have a constant presence throughout the care and illness trajectory [60]. Consistently across family-centered care models, families were seen as vital members of the care team [38] who provide emotional, physical, and instrumental levels of support to the patient [32, 54].

Family strengths

Three of the models underscored that family-centered intendance is based on a belief that all families have unique strengths that should be identified, enhanced, and utilized [41, 53, 66]. Models identified various examples of family strengths in care commitment including resilience [41], coping strategies [58], competence and skill in providing care [25, 26] and motivation [49]. None of the models discussed how these strengths would exist identified when implementing family centered intendance. Three of the models stated that family unit-centered care should continuously encourage caregivers to utilize these strengths [53, 57, 64] although specific examples of how to exercise so were not included. Identifying areas of weakness that may require pedagogy and training was not discussed in the models.

Cultural values

Families were thought to contribute to a culturally sensitive intendance program by discussing their specific cultural needs, equally well as their strengths related to personal values, preferences and ideas. Caregivers' social, religious, and/or cultural backgrounds can influence the provision of care to their family member [29, 49, 57, 58]. One model suggested that HCPs need to elicit information about families' beliefs [26] to help guide culturally sensitive care plans (e.g. religious participation). The process by which this would occur was non discussed in detail.

Dedicated policies and procedures to support implementation

To support implementation, family-centered intendance models should have defended policies and procedures that are besides transparent [56, 67, 68]. Both the macro and micro levels of society need to exist considered when trying to implement family-centered practices [13]. Perrin and colleagues [xiii] described macro level issues equally including regime policies and agencies (e.thou., national, provincial, municipal), while micro level factors include community service systems (e.g., physicians, other HCPs, schools, public transportation, etc.). Examples of macro-level considerations include incorporating families in nation-broad policy making and program development [29, 53, 56, 60]. Micro-level considerations include incorporating family members and patients in decision-making for local community organizations [69], the implementation of health programs and intendance policies at regional hospitals, as well as in HCP education [29].

Family unit-centered intendance policies were identified as important as they legitimize and back up families' contributions to the care of their family member. For example, in pediatrics, Regan and colleagues [39] suggested irresolute policy to open visitation hours to increment family members' roles as partners in care. This could increase the number of interactions betwixt HCPs, patients and families, and, as a result, farther support caregivers in their caring role [24].

Family-centered intendance models also noted the importance of considering the physical surround when developing policies and practices. The concrete environment of intendance settings should be created and tailored to meet the needs of patients and families [54], although concreate examples were not provided. Both the patient and family should exist included in the development and evaluation of facility design [29], where possible, as well as modifications to the domicile environment.

Give-and-take

The purpose of this scoping review was to place core components of family-centered care models and to place components that are universal and can be practical across intendance populations. This paper likewise aimed to identify gaps in the literature to provide recommendations for futurity research. Most models were developed for pediatric populations with a number of models emerging for the intendance of adult populations. The synthesis suggests that at that place are cadre components of family-centered care models that were not unique to specific illness populations or care contexts making them applicable beyond diverse health weather condition and experiences. From a theoretical perspective, our review adds to our understanding of how FCC is conceptualized within the current state of the literature and suggests the possibility of moving towards a universal model of FCC. This includes developing a care plan with defined outcomes and that incorporates patient and family perspectives and their unique characteristics. This likewise includes collaboration between HCPs and family unit members and flexible policies and procedures. Withal, in that location were some aspects of models that were specific to illness populations such as illness-specific patient and family pedagogy.

Currently, person-centered care is considered best practice for improving care and outcomes for many illness populations. Patient-centered intendance has been described as beingness "respectful of and responsive to individual patient preferences, needs and values, and ensuring that patient values guide all clinical decisions" [70]. Person-centered care involves: acknowledging the individuality of persons in all aspects of care, and personalizing care and surroundings; offering shared decision making; interpreting beliefs from the person'south viewpoint; and prioritizing relationships to the same extent as care tasks [71]. Aspects of patient and person-centered care were identified equally key components of family-centered intendance models including focusing on patient and family values, preferences and needs, related to their own circumstances and family unit contexts. In addition, this review identified specific components that go beyond patient-centered care that are required to address the needs of families including focusing on respectful communication to facilitate the necessary patient/family unit-professional partnerships and collaboration needed to develop and implement intendance plans. Moreover, there is the demand for the patient/family-professional person partnerships to respect the strengths, cultures and expertise that all members of this partnership bring to the evolution and delivery of care plans.

Implementation of disease-specific models of care for multiple different illnesses may be challenging for health care systems. Equally many individuals live with multi-morbidity, a non-illness specific family-centered care model may meet the needs of more individuals [72]. Yet, in that location is a lack of discussion in the literature of concrete strategies to help implement the central concepts identified in our review. Moreover, the research on implementing FCC models in real world situations is scant. In club to encourage changes in health care systems there is a need for testify that the concepts of FCC lead to improvements.

This review identified aspects of family unit-centered care that are disease-specific. Illness-specific education and support is required at each stage of the affliction recognizing differences in affliction trajectories beyond patient populations [73]. Currently, the models are described with static concepts that are not reflective of ongoing and changing illness trajectories. Providing illness-specific care, advice, and information that is sensitive to their place in the affliction trajectory may greatly influence caregivers' capacity to support the care recipient. Further inquiry is needed to understand how family unit-centered intendance may evolve beyond the affliction and intendance trajectory.

More research is needed to enhance the potential of a universal family unit-centered intendance model that crosses age groups, weather condition, and care settings. For instance, in the current models of FCC, there is not consistent definition of what constitutes the family. In the pediatric literature the family primarily includes the parents of the kid, but does not usually include siblings or extended family members who may exist providing care. Moreover, electric current FCC models fail to address disharmonize and mediation for circumstances where there is the potential for family unit members to disagree with i another, with the patient or with the HCPs regarding care plans or other aspects of intendance.

Equally many of the models were developed for pediatric populations, they neglect to acknowledge aspects such equally privacy issues and cerebral capacity. These bug become relevant as we consider models of care for adult populations. In instances where patients' cognitive capacity influences their ability to participate in decision-making, family caregivers become active contributors to intendance plan development and implementation. Caregivers can benefit from having admission to patients' medical information to contribute to treatment determination making and inform care and service apply. Current privacy legislation does not automatically give families access to relevant information. Future research should explore adult patients' preferences for family members to have access to their medical records, every bit their preferences volition influence the management of privacy in models of FCC.

Lastly, the articles included in this review were primarily descriptive and non evaluative. Evaluations are needed to demonstrate the benefit of FCC to patient, caregiver and health system outcomes. Potential evaluation outcomes tin include satisfaction with intendance, improvements in patient wellness and caregiver health and stress, and efficient use of health services. There should be consensus regarding outcome measures to be used when evaluating FCC models to enhance our power to compare beyond models. Model evaluation is needed to provide empirical evidence to support or reject the concepts of FCC in both universal and affliction-specific contexts. Moreover, we need methods to assess implementation of FCC in practise. For example, measures to assess the family-centered nature of care are beingness developed [24,25,26]. The review suggests we may need new assessment tools to assess, for case, family strengths.

Concrete steps are needed to implement a universal FCC care model into practice. While we have divers the components of a model, we have besides highlighted additional empirical research that is needed to farther define model components in real-world settings, within and across various care contexts and disease populations. In particular, we recommend the testing of our universal model in the context of a randomized command trial (RCT).

Lastly, we recommend the evolution of outcomes measures to determine if FCC leads to improvements in patient and family satisfaction, mental and physical health outcomes, enhanced efficiency, wellness system utilization (eastward.m., decreased length of hospital stay or return hospital visits), community reintegration and cost-effectiveness. Of import outcomes should relate to families, patients of all ages and wellness intendance professionals. Outcome measures related to wellness care professionals may include enhanced comfort working with families and patients. Valid and reliable measures are essential for the evaluation of a model's effectiveness and to translate FCC models into do.

Written report limitations

This scoping review is non without limitations. But published, English linguistic communication articles were included, thus excluding other models that may exist in other languages. This may have also limited models to those that were developed and/or tested in predominantly English-speaking counties. We too did not explore greyness literature, limiting our models to simply those that underwent peer review. Many of the included models were designed for the pediatric population, then findings have limited application to adult populations.

Conclusion

This paper used an established scoping review methodology to synthesize 55 models of family-centered care. We were able to make up one's mind the universal components of the models that place both the patient and family at the eye of care, regardless of the patient's illness or intendance context. Findings outline aspects of FCC that are universal and aspects that are illness specific. Universal aspects include collaboration between family members and health intendance providers to define care plans that take into consideration the family unit contexts. It besides includes the need for flexible policies and procedures and the need for patient, family, and wellness care professional education. Not-universal aspects include illness-specific patient and family unit didactics. Future inquiry should evaluate the power of FCC to improve important patient, family, caregiver, and health system outcomes. Wellness care policies and procedures are needed that comprise FCC to create arrangement level modify. Our review moves the field of FCC forward by identifying the universal and disease-specific model components that tin inform model development, testing, and implementation. Advancing FCC has the potential to optimize outcomes for patients, families, and caregivers.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- FCC:

-

Family unit-centered intendance

- HCPs:

-

Health care professionals

References

-

Sinha Yard. Portrait of caregivers, 2012. Ottawa: Statistics Canada; 2013. Retrieved from:http://healthcareathome.ca/mh/en/Documents/Portrait%20of%20Caregivers%202012.pdf

-

Brodaty H, Donkin Thousand. Family caregivers of people with dementia. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2009;11(2):217.

-

Schulz R, Martire LM. Family caregiving of persons with dementia: prevalence, health effects, and back up strategies. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2004;12(3):240–9.

-

Collins LG, Swartz K. Caregiver care. Am Fam Physician. 2011;83(xi):1309.

-

Zarit SH, Reever KE, Bach-Peterson J. Relatives of the impaired elderly: correlates of feelings of brunt. The Gerontologist. 1980;20(half-dozen):649–55.

-

Government of Canada. Canada Wellness Act ["CHA"], R.Southward.C. 1985, c. C-6. Ottawa, Retrieved from https://spider web.archive.org/web/20031205153216/http://laws.justice.gc.ca/en/C-half dozen/

-

Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care. Ontario's Aging at Home Strategy. Toronto: Ministry of Wellness and Long-Term Care; 2007. Retrieved from: http://www.health.gov.on.ca/english/public/ program/ltc/33_ontario_strategy.html

-

Carers Canada. Canada'due south Carer strategy. Ottawa. Retrieved from: http://world wide web.carerscanada.ca/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/CC-Caregiver-Strategy_v4.pdf.

-

Feinberg LF, Newman SL. A written report of 10 states since passage of the National Family Caregiver Back up Plan: policies, perceptions, and program development. The Gerontologist. 2004;44(6):760–9.

-

Hokenstad MC Jr, Restorick RA. International policy on ageing and older persons: implications for social work practice. Int Soc Piece of work. 2011;54(3):330–43.

-

Sweden Written report, Supra notation 20, sat 9; social services act, SFS 2001:453, promulgated June 7, 2001, online: Ministry building of Health and Social Diplomacy, Sweden.

-

Institute for Patient- and Family-Centered Intendance. What is patient- and family-centered care? Available at: http://world wide web.ipfcc.org/about/pfcc.html

-

Perrin JM, Romm D, Bloom SR, Homer CJ, Kuhlthau KA, Cooley C, Duncan P, Roberts R, Sloyer P, Wells Northward, Newacheck P. A family-centered, community-based system of services for children and youth with special health intendance needs. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2007;161(10):933–six.

-

Gilmer MJ. Pediatric palliative care. Crit Care Nurs Clin North Am. 2002;fourteen(2):207–14.

-

MacKean G, Spragins W, L'Heureux L, Popp J, Wilkes C, Lipton H. Advancing family-centred care in kid and adolescent mental wellness. A disquisitional review of the literature. Healthc Q. 2012;15:64–75.

-

Chu S, Reynolds F. Occupational therapy for children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), role 2: a multicentre evaluation of an assessment and handling packet. Br J Occup Ther. 2007;70(10):439–48.

-

Johnson SK, Arts and crafts Yard, Titler M, Halm Thousand, Kleiber C, Montgomery LA, Megivern K, Nicholson A, Buckwalter One thousand. Perceived changes in adult family unit members' roles and responsibilities during critical illness. J Nurs Scholarsh. 1995;27(3):238–43.

-

Visser-Meily A, Postal service M, Gorter JW, Berlekom SB, Van Den Bos T, Lindeman Due east. Rehabilitation of stroke patients needs a family-centred approach. Disabil Rehabil. 2006;28(24):1557–61.

-

Teno JM, Casey VA, Welch LC, Edgman-Levitan Due south. Patient-focused, family unit-centered finish-of-life medical care: views of the guidelines and bereaved family members. J Hurting Symptom Manag. 2001;22(3):738–51.

-

Gagliardi AR, Berta Due west, Kothari A, Boyko J, Urquhart R. Integrated noesis translation (IKT) in health care: a scoping review. Implement Sci. 2015;11(1):38.

-

Arksey H, O'Malley 50. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol. 2005;8(1):nineteen–32.

-

The Bureau for Clinical Innovation (ACI). Understanding the process to develop a Model of Intendance: An ACI Framework. A practical guide on how to develop a Model of Care . 2013 May [cited 2018 April 27]. Available from: https://world wide web.aci.health.nsw.gov.au/__data/avails/pdf_file/0009/181935/HS13-034_Framework-DevelopMoC_D7.pdf

-

Levac D, Colquhoun H, O'Brien KK. Scoping studies: advancing the methodology. Implement Sci. 2010;five(one):69.

-

Marcenko MO, Smith LK. The impact of a Fmaily-centered case direction approach. Soc Piece of work Health Care. 1992;17(i):87–100.

-

Kissane D. Family focused grief therapy: the role of the family unit in preventive and therapeutic bereavement care. Bereave Intendance. 2003;22(ane):6–8.

-

Kissane D, Lichtenthal WG, Zaider T. Family intendance before and after bereavement. Omega. 2008;56(1):21–32.

-

Leviton A, Mueller M, Kauffman C. The family unit-centered consultation model: applied applications for professionals. Infants Young Child. 1992;4(3):1–viii.

-

Sharifah WW, Nur HH, Ruzita AT, Roslee R, Reilly JJ. The Malaysian childhood obesity handling trial (MASCOT). Malays J Nutr. 2011;17(2):229–36.

-

Jasovsky DA, Morrow MR, Clementi PS, Hindle PA. Theories in action and how nursing practice changed. Nurs Sci Q. 2010 Jan;23(i):29–38.

-

Darrah J, Law K, Pollock N. Family unit-centered functional therapy-a choice for children with motor dysfunction. Infants Young Child. 2001;13(four):79–87.

-

Dowling J, Vender J, Guilianelli S, Wang B. A model of family unit-centered care and satisfaction predictors: the critical care family unit help program. Chest. 2005;128(3):81S–92S.

-

Madigan CK, Donaghue DD, Carpenter EV. Development of a family liaison model during operative procedures. MCN Am J Matern Child Nurs. 1999;24(4):185–ix.

-

Sisterhen LL, Blaszak RT, Woods MB, Smith CE. Defining family-centered rounds. Teach Learn Med. 2007;19(3):319–22.

-

Hyman D. Reorganizing wellness systems to promote best practice medical intendance, patient self-management, and family-centered intendance for childhood asthma. Ethnicity & disease. 2003;13(three Suppl three):S3–94.

-

Kaufman J. Example management services for children with special health care needs. A family-centered arroyo. J Case Manag. 1992;1(2):53–6.

-

Prelock PA, Beatson J, Contompasis SH, Bishop KK. A model for family-centered interdisciplinary practice in the community. Meridian Lang Disord. 1999;19(iii):36–51.

-

Cormany EE. Family-centered service coordination: a iv-tier model. Infants Young Child. 1993;6(two):12–nine.

-

King K, Tucker MA, Baldwin P, Lowry K, Laporta J, Martens Fifty. A life needs model of pediatric service delivery: services to support community participation and quality of life for children and youth with disabilities. Phys Occup Ther Pediatr. 2002;22(two):53–77.

-

Regan KM, Curtin C, Vorderer L. Prototype shifts in inpatient psychiatric care of children: approaching child-and family-centered intendance. J Child Adolesc Psychiatr Nurs. 2006;19(1):29–40.

-

McKlindon D, Barnsteiner JH. Therapeutic relationships: development of the Children's Hospital of Philadelphia model. MCN Am J Matern Child Nurs. 1999;24(5):237–43.

-

Romero-Daza Due north, Ruth A, Denis-Luque M, Luque JS. An culling model for the provision of services to hiV-positive orphans in Haiti. J Health Intendance Poor Underserved. 2009;twenty(iv):36–twoscore.

-

Muething SE, Kotagal UR, Schoettker PJ, del Rey JG, DeWitt TG. Family-centered bedside rounds: a new arroyo to patient intendance and teaching. Pediatrics. 2007;119(4):829–32.

-

Raina P, O'Donnell M, Rosenbaum P, Brehaut J, Walter SD, Russell D, Swinton Thousand, Zhu B, Forest E. The health and well-being of caregivers of children with cognitive palsy. Pediatrics. 2005;115(half dozen):e626–36.

-

Hernandez LP, Lucero E. Days La Familia community drug and alcohol prevention program: family unit-centered model for working with inner-metropolis Hispanic families. J Prim Prev. 1996;sixteen(iii):255–72.

-

MacFarlane MM. Family centered care in adult mental health: developing a collaborative interagency practice. J Fam Psychother. 2011;22(ane):56–73.

-

Mausner S. Families helping families: an innovative arroyo to the provision of respite intendance for families of children with circuitous medical needs. Soc Work Health Care. 1995;21(1):95–106.

-

Biggert RA, Watkins JL, Melt SE. Home infusion service delivery system model: a conceptual framework for family unit-centered care in pediatric home intendance delivery. J Intraven Nurs. 1992;15(4):210–eight.

-

Prizant BM, Wetherby AM, Rubin E, Laurent Air-conditioning. The SCERTS model: a transactional, family-centered approach to enhancing communication and socioemotional abilities of children with autism spectrum disorder. Infants Young Kid. 2003;16(four):296–316.

-

Goetz DR, Caron W. A biopsychosocial model for youth obesity: consideration of an ecosystemic collaboration. Int J Obes. 1999;23(S2):S58.

-

Byers JF. Holistic acute intendance units: partnerships to see the needs of the chronically I11 and their families. AACN Adv Crit Intendance. 1997;8(2):271–9.

-

Constabulary Grand, Darrah J, Pollock Northward, King G, Rosenbaum P, Russell D, Palisano R, Harris S, Armstrong R, Watt J. Family-centred functional therapy for children with cognitive palsy: an emerging practice model. Phys Occup Ther Pediatr. 1998;18(1):83–102.

-

Brady MT, Crim L, Caldwell 50, Koranyi K. Family-centered intendance: a paradigm for care of the HIV-affected family. Pediatr AIDS HIV Infect. 1996;vii(3):168–75.

-

Tyler Do, Horner SD. Family-centered collaborative negotiation: a model for facilitating behavior change in chief care. J Am Assoc Nurse Pract. 2008;20(iv):194–203.

-

Dark-brown Thousand, Mace SE, Dietrich AM, Knazik S, Schamban NE. Patient and family–centred care for pediatric patients in the emergency department. CJEM. 2008;x(1):38–43.

-

Attharos T. Development of a family unit-centered care model for the children with cancer in a pediatric cancer unit. Thailand: Mahidol University; 2003.

-

Baker JN, Barfield R, Hinds PS, Kane JR. A process to facilitate decision making in pediatric stem cell transplantation: the individualized care planning and coordination model. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2007;thirteen(3):245–54.

-

Lyon ME, Garvie PA, Briggs L, He J, McCarter R, D'Angelo LJ. Development, feasibility, and acceptability of the family unit/adolescent-centered (FACE) accelerate care planning intervention for adolescents with HIV. J Palliat Med. 2009;12(4):363–72.

-

Beers LS, Cheng TL. When a teen has a tot: a model of care for the adolescent parent and her child: you tin mitigate the health and educational risks faced past an boyish parent and her child by providing a medical abode for both. This" teen-tot" model of family unit-centered care provides a framework for success. Contemp Pediatr. 2006;23(four):47–52.

-

Callahan HE. Families dealing with advanced centre failure: a challenge and an opportunity. Crit Care Nurs Q. 2003;26(3):230–43.

-

Connor D. Family-centred care in practice. Nurs N Z. 1998;4(4):18.

-

Martin-Arafeh JM, Watson CL, Baird SM. Promoting family-centered care in loftier take a chance pregnancy. J Perinat Neonatal Nurs. 1999;xiii(i):27–42.

-

Tluczek A, Zaleski C, Stachiw-Hietpas D, Modaff P, Adamski CR, Nelson MR, Reiser CA, Ghate S, Josephson KD. A tailored approach to family unit-centered genetic counseling for cystic fibrosis newborn screening: the Wisconsin model. J Genet Couns. 2011;xx(2):115–28.

-

Kavanagh KT, Tate NP. Models to promote medical health intendance delivery for indigent families: computerized tracking to example management. J Health Soc Policy. 1990;2(i):21–34.

-

Ainsworth F. Family centered grouping care practice: model building. In Child and youth care forum 1998 February 1 (Vol. 27, no. 1, pp. 59-69). Kluwer Academic Publishers-Human Sciences Press.

-

Ahmann E, Bond NJ. Promoting normal development in school-historic period children and adolescents who are technology dependent: a family centered model. Pediatr Nurs. 1992;18(iv):399–405.

-

Grebin B, Kaplan SC. Toward a pediatric subacute care model: clinical and authoritative features. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1995;76(12):SC16–20.

-

Kazak AE. Comprehensive care for children with cancer and their families: a social ecological framework guiding research, do, and policy. Kid Serv Soc Policy Res Pract. 2001;4(four):217–33.

-

Davison KK, Lawson HA, Coatsworth JD. The family-centered action model of intervention layout and implementation (FAMILI) the case of babyhood obesity. Health Promot Pract. 2012;thirteen(four):454–61.

-

Monahan DJ. Assessment of dementia patients and their families: an ecological-family-centered arroyo. Health Soc Piece of work. 1993;18(2):123–31.

-

Reid Ponte PR, Peterson K. A patient-and family-centered care model paves the fashion for a culture of quality and safety. Crit Intendance Nurs Clin. 2008;xx(iv):451–64.

-

Ekman I, Swedberg K, Taft C, Lindseth A, Norberg A, Brink Due east, Carlsson J, Dahlin-Ivanoff Due south, Johansson IL, Kjellgren K, Lidén E. Person-centered care—ready for prime fourth dimension. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2011;x(4):248–51.

-

Uijen AA, van de Lisdonk EH. Multimorbidity in main intendance: prevalence and trend over the last 20 years. The European journal of full general practise. 2008;xiv(sup1):28–32.

-

Cameron JI, Gignac MA. "Timing it right": a conceptual framework for addressing the support needs of family caregivers to stroke survivors from the infirmary to the home. Patient Educ Couns. 2008;lxx(3):305–xiv.

Acknowledgements

K. Naglie is supported by the George, Margaret and Gary Hunt Family Chair in Geriatric Medicine, University of Toronto.

We would similar to thank and acknowledge the contributions of Jessica Babineau, Information Specialist at the Toronto Rehabilitation Found - University Health Network, for providing guidance on the search strategy evolution, and conducting the literature search.

We would like to give thanks and admit the contributions of Jazmine Que. and John Nguyen, Masters of Occupational Therapy Students- The University of Toronto, for reviewing subsets of the retrieved manufactures and extracted written report data.

Writer data

Affiliations

Contributions

KMK and JIC conceptualised and designed the study. KMK, JIC, GN and MAMG contributed to the interpretation of the data and to the drafting of the initial and revised manuscripts. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ideals approval and consent to participate

Not applicable

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Annotation

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Additional files

Rights and permissions

Open Access This commodity is distributed under the terms of the Artistic Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted utilise, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Eatables license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/cypher/1.0/) applies to the information made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

Reprints and Permissions

Almost this article

Cite this article

Kokorelias, K.Thou., Gignac, M.A.M., Naglie, One thousand. et al. Towards a universal model of family centered intendance: a scoping review. BMC Health Serv Res nineteen, 564 (2019). https://doi.org/x.1186/s12913-019-4394-5

-

Received:

-

Accepted:

-

Published:

-

DOI : https://doi.org/ten.1186/s12913-019-4394-five

Keywords

- Caregivers

- Family centered care

- Family unit caregiving

- Patient-care

- Patient education

- Scoping review

Source: https://bmchealthservres.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12913-019-4394-5

0 Response to "History of Family-centered Care and Family Systems Theory"

Post a Comment